Author: He Yifan, Deputy Editor-in-Chief of China Entrepreneur

The year 2023 has arrived. As the world rang out the old and rang in the new, I went on frequent work trips to several cities, and everywhere I went, I felt the surging vitality. While 2022 was a year of stabilization as we worked to stabilize industrial and supply chains, employment, prices, and the broader economy, and to ensure people’s livelihoods, 2023 may be about moving forward: The “three carriages” of China’s economic growth—consumption, investment, and exports—will possibly see a U-shaped rebound driven by accelerated digital intellectualization, profound transformation of brick-and-mortar businesses, and a new wave of integrated innovations.

In conversations with a number of entrepreneurs, there is talk of “pessimism” and “optimism”, and they all agree that pessimists may be closer to being right, but optimists are closer to being successful. Among the eternal optimists is Xie Weishan, president of Kmind Strategy Consulting. As a footnote to his optimism, “Kmind Strategy Consulting” was renamed “Kmind 10-Billion Strategy”: He believes that China will produce more “10-billion” companies, and that this is the bedrock of a healthy economy.

Over the past three years, Weishan has developed a new habit: practicing Standing Stake. By the time he finishes his daily hour-long exercise, he is drenched in sweat, feeling comfortable and at ease.

As an important excise in Tai Chi, Standing Stake, or “Zhan Zhuang” in Chinese, consolidates the foundation, cultivates vitality, and keeps your blood flowing smoothly. This is also what Weishan hopes to achieve with large-scale companies, meaning those with annual revenue of more than 10 billion yuan. He believes “10 billion” is the critical tipping point for growth. One step forward leads you to the big picture and great prospects, while one step back can cause you to slide into mediocrity and lose the ability to even sustain your business.

When Xie Weishan launched into corporate strategy consulting in 2015, it did not seem like a popular track. Strategy consulting was all the rage in the 1990s, when experts from McKinsey, PwC, BearingPoint, Inc., Accenture, and other international consulting firms were guests of prominent Chinese companies. On November 7, 2012, Monitor Group, co-founded by management guru Michael Porter, filed for bankruptcy protection, marking a watershed moment in the history of strategy consulting. Over the next decade, the niche continued to decline, with some large companies downsizing their strategy consulting departments, marginalizing them, or eliminating them altogether. As a Chinese proverb goes, “Even an accomplished physician cannot cure himself”. The inability to help themselves has become almost a curse for strategy consulting firms.

But the decline of strategy consulting does not mean the decline of strategy. Indeed, strategic thinking is of particular importance in the “VUCA” (volatility, uncertainty, complexity, and ambiguity) age, without which we would end up running out of luck at the edge of a cliff like a blind man riding on the back of a blind horse. Weishan tries to break the spell cast upon strategy consulting with “Chinese kung fu”. He knows by heart Sun Tzu’s The Art of War, a crucial piece of his underlying logic puzzle.

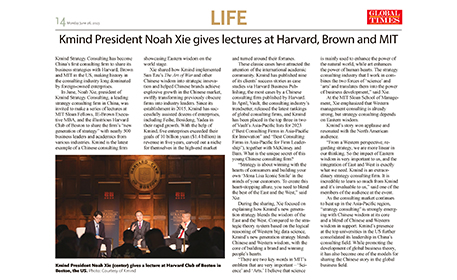

The corporate world is keen on The Art of War. What’s unique about Weishan is his ability to not only talk the talk but walk the walk, proving the effectiveness of Sun Tzu’s strategies and tactics with success cases such as FIRMUS, Bosideng, Yadea, Angel, Joeone, and Gongniu. Nine of Kmind’s case studies have been featured in the case database of Harvard Business Publishing (HBP) Education since 2020. This is a valuable achievement because, as a benchmark for international case studies, the HBP Education case library selects only the best cases.

In his new book, Re-understanding Entrepreneurship, Professor Zhang Weiying summarizes the functions of entrepreneurs into two: arbitrage and innovation. Arbitrage is about finding imbalances within existing technical conditions, seeking profitable opportunities, and exploiting them. Whereas, innovation is the creation of an imbalance, the invention of something that wasn’t there before, and the commercialization of it. Weishan’s “kung fu” skills are frankly not of much use in an arbitrage-oriented market. But for those wanting to get out of the rat race and move from confusion to clarity in a market dominated by innovation, his theories and practices are worth studying.

Here are a few key takeaways from a recent exchange between us:

1. When others are keeping their heads down, companies that dare to pass on new ideas and launch new campaigns will be better recognized, as there is less noise in the market. Whatever the circumstances, lying flat, or going “Goblin mode”, is never the best option. A well-timed shot may instead lead to unexpected growth.

2. A brand is to an entrepreneur what a commander’s tally is to a general. Without it, they would not be able to command their troops.

3. Ten billion revenue is a ticket to a sustainable future and thereby a chance to compete in the global market. Companies of that size boast highly efficient use of resources and a positive impact on society in return for the resources they acquire.

4. Companies tend to do too much, not too little. Streamlining and pruning can be difficult, but almost every company can cut half its SKUs with their eyes closed and nothing will go wrong.

5. The Art of War appears to be directionless and vague, but upon closer examination is certainly meaningful and insightful. You have to let it grow on you and get in touch with its true essence. Instead of seeking quick success and instant benefits, allow it to inspire and enlighten you. The less purposeful and utilitarian you are, the better you will be at putting it to use.

6. A careful and earnest reader of The Art of War will feel humbled and less self-righteous. You know what leads to failure when you’ve read it thoroughly.

The following is an edited version of the conversation between China Entrepreneur and Xie Weishan.

1.A brand is like a commander’s tally.

China Entrepreneur: Let’s talk about 2022. Many entrepreneurs have mixed feelings about the year. If you had to sum it all up in one word, what would it be?

Xie Weishan: Unusual. It’s been a very unusual, very difficult year for businesses. We even made a short video to commemorate those days.

How was it unusual? First of all, many national chain stores in China were closed up to 20 percent of the time, which certainly had unusual implications for business. Internationally, the combination of the Russo-Ukrainian War, the inflation surge of the century in the United States and across Europe, and concerns about the macroeconomic situation was also unusual. Lastly, the question of what to do next remains unanswered: should we move steadily or should we tighten our belts?

CE: Sometimes when a company weathers a crisis, a new “node” of opportunity is created in its growth, much like the nodes on a bamboo stalk that make it stronger and more resilient, as Mr. Inamori Kazuo said. What qualities do you observe in companies that help them thrive in this “unusual” environment?

Weishan: First of all, it’s important to maintain an optimistic can-do mindset. Stay committed, passionate, and motivated in the face of adversity. These qualities are valuable assets for a company. Second, think clearly. This is a time when blindly pushing ahead can be risky, and having a well-organized and structured strategy is key.

A positive example is Bosideng. Their collection of ultralight down jackets for 2022 caused a stir in the industry and helped it win back younger consumers. The sales figures were truly impressive despite a sluggish economy. That same year, as people spent more time at home due to the lockdown, celebrities were showing off their cooking skills online. Gongniu responded to this trend by rolling out a track socket, a next-generation kitchen socket with a base that separates from the adapter. It won the market’s attention.

CE: The two cases you just mentioned are very typical. Both are established companies with conventional products. How did they manage to find a second growth curve?

Weishan: Being established is actually an advantage, as consumers are more likely to trust them when they innovate in their own area of expertise. They can capitalize on a reputation built up over the years in the market.

Second, established companies can amaze and surprise consumers when they play with new ideas.

Third, when most brands were keeping their heads down in 2022, companies that dared to pass on new ideas and launch new campaigns were actually better recognized, as there was less noise in the market.

Even if it’s not ideal out there, lying flat, or going “Goblin mode”, is never the best option. A well-timed shot may instead lead to unexpected growth.

As Sun Tzu said in The Art of War, “military tactics are like unto water”. And just as water shapes its course according to the nature of the ground over which it flows, a company should also maintain its flexibility. When everyone else is pulling back and swarming in one direction, it may be crucial that you do the opposite.

CE: As someone familiar with The Art of War, what role do you think a brand plays in the competition between companies?

Weishan: A brand is to an entrepreneur what a commander’s tally is to a general. Without it, they would not be able to command their troops. Just as a commander’s tally is a token of power, a brand is the core asset of a business.

CE: The awakening of brand awareness among Chinese entrepreneurs has taken a while. How widespread is it now?

Weishan: Many entrepreneurs know how important branding is, but lack the tools for it. They typically do not really invest in their brand. They are willing to spend money on machinery, equipment, and land because these are tangible. But when it comes to building a brand, they tend to tighten their purse strings.

CE: What is the relationship between a brand and a 10-billion strategy?

Weishan: Having a brand is an essential element in a 10-billion strategy. Ten billion is but a manifestation; the path to victory lies in the minds and hearts of consumers. As described by Sun Tzu, the path is powerful, albeit invisible. It manifests as your brand and credibility for which we are willing to do anything.

2. “10-billion” companies are the bedrock of a healthy economy.

CE: Why “10 billion”? What makes it symbolic?

Weishan: “10 billion” is a specific number and the embodiment of a company’s performance at its best. China now has 1,380 sub-industries, many of which can support a 10-billion company.

Looking back on the past 20 years, the number of large-scale private enterprises increased from just 2 in 2000 to 126 in 2010 and 1044 in 2021. Simultaneously, China’s GDP grew from 10 trillion yuan in 2000 to 114.92 trillion yuan in 2021, a 10-fold increase. You can see a positive correlation between the two. So, I proposed the “10-billion strategy” in the hope that more Chinese companies will see such opportunities.

Ten billion revenue is a ticket to a sustainable future and thereby a chance to compete in the global market. Reaching 10 billion yuan in revenue is not easy. Compared with billion-yuan companies, 10-billion ones operate in a more systematic manner and are better at developing strategies and building teams. It’s possible to achieve a scale below 10 billion by sheer luck, but when you hit 10 billion, you’ve got to know something.

Companies of that size boast highly efficient use of resources and a positive impact on society in return for the resources they acquire. Such large-scale enterprises fit into the Chinese market and help stabilize the economy. They are talent magnets with relatively robust systems, better employee protection, and rational use of resources. The number of 10-billion companies indicates the health of an economy.

CE: When is a business most likely to fail on its way to hitting a 10 billion revenue target? Or is there a stage where they just stop growing?

Weishan: Many companies are stuck at the billion-yuan level, which is very dangerous. It suggests their lack of a better way to achieve further growth. If they are overtaken by their peers at this stage, the result will be catastrophic.

A common mistake for companies to make in this process is reckless diversification, where they try to piece together a 10-billion business with multiple segments and end up rushing into unfamiliar territories. The best tactic, according to The Art of War, is to “defeat the enemy by concentrating your energy and resources on one key area”. If you can hit the 10-billion mark by focusing on one business, one product, or one industry, you are actually generating the greatest value for your company.

CE: I’m sure entrepreneurs are all smart enough to be responsible with their money and their companies, and the reason behind their diversification moves could be to spread the risk.

Weishan: You have to go against human instincts in pursuing large-scale transformation. As the saying goes, never put all your eggs in one basket. It’s human nature to think that growing multiple businesses is the safest option.

But we need to overcome such weaknesses and trust that it’s safe to put all our eggs in one basket, because today’s business environment is not what it was in the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, companies were rushing to stake a claim in new markets, sometimes simply by launching new production lines, as there was huge room for arbitrage. But now, when every track is overcrowded with competitors, you are more likely to win by focusing all your energy and resources on a single track.

3. Less is more.

CE: I recently discussed with some friends that at this stage, Chinese entrepreneurs may need to transition from “animal spirits” to “plant spirits”. “Animals” are more aggressive, move fast, and go where there is profit, and that’s fine. But now we may be encouraging more of a plant-based spirit, rooted deep, seemingly immobile, yet resilient and ecologically friendly. Are companies with a strong plant sprit more likely to make it to the 10-billion mark?

Weishan: That’s a very good analogy. Indeed, there is power in “plant spirits” representing an entrepreneur’s courage to stick to long-termism, to take root in his industry, and to bet his life on it. Similarly, I admire what Sun Tzu said: “Stand firm and unshakeable like a mountain and keep your plans and actions secret.” Like plants, entrepreneurs should stay calm and collected and be willing to spend years single-mindedly polishing their skills and abilities. But real war is brutal, and you have to react quickly and when necessary. That’s why Sun Tzu added that when we attack, we “attack with the fury of fire and take bold and swift action”, which is the embodiment of “animal spirits”. In a word, we should combine plant spirits with animal spirits.

CE: Normally, people prefer addition because it’s gratifying and they know where to target, but you pick up a “scalpel” and you’re mostly doing subtraction for them.

Weishan: Almost 100 percent subtraction and very little addition. Companies tend to do too much, not too little. Streamlining and pruning can be difficult, but like Yadea, FIRMUS, and Bosideng, almost every company can cut half its SKUs with their eyes closed and nothing will go wrong.

Subtraction is certainly painful and you have to tell people why it works. Pay attention to how you make your choices. This is usually done by increasing the scale of new products first and then optimizing the existing ones, rather than cutting them from the very beginning. Trimming begins after you’ve secured the first win with additional products. And start with things that are completely unprofitable and small in volume. For listed companies, subtraction should be adjusted based on their annual financial results.

Most importantly, you should find out where your growth spurt is coming from, what products have the highest ROI, what products bring in quick profits, and how to get results quickly. Once you have your results, you will find it much easier to axe what is unnecessary.

CE: The word “strategy” is a Western invention, but you reinterpret it with a lot of Eastern wisdom.

Weishan: What is strategy? As the ancient Chinese saying goes, “The one who wins the hearts of the people wins the world.” In plain English, a company wins the market by building a brand that resonates with the minds of consumers. This has been advocated by the Chinese for thousands of years, and I think it’s a good way to look at strategy.

Meanwhile, strategy consulting based on Western theory has entered a period of confusion and muddle. Unlike strategy consulting, management consulting handles relatively stable and often controllable parameters, making it well suited to the Western theory’s quest for precision, logic, and data. Strategy consulting, on the other hand, deals with variables. In the VUCA age and in highly complex markets like China, strategy consulting based on the Western quantitative approach will not amount to much.

The Eastern mindset takes a holistic approach to thinking, with a focus on images rather than logic, and draws upon intuition and an artful mastery of aptness to pursue what is approximately right. It has the potential to shine in strategy consulting.

For example, in directing a battle, Sun Tzu argued that “military tactics are like unto water”. Seemingly illogical and unscientific, this is in fact an analogy: Just as water runs away from high places and hastens downwards, the way in war is to avoid what is strong and to strike at what is weak, mapping out the route according to the actual conditions and working out victory in relation to the foe you are facing. With today’s global business landscape being more akin to a warzone of competition, The Art of War finds itself more relevant than ever before, and its wealth of Eastern strategic insight will help revolutionize strategy consulting for good.

CE: In terms of strategy, is it better to be as clear as possible or “approximately right”?

Weishan: Strategy is essentially about pinpointing certainty and seeking what is “approximately right” in the midst of uncertainty and ambiguity. It values the art of aptness and, rather than relying on a data-driven, quantitative approach alone, it’s a combination of both.

4. Do not read The Art of War for the sake of quick success.

CE: Can you share with us some specific examples of how The Art of War, as a book on the philosophy of war, can be applied in practice?

Weishan: The Art of War consists of 13 chapters with a total of over 6,000 words. It does not discuss any specific tactics. Rather, it’s more about providing enlightenment and inspiration. New discoveries are made with each reading.

There is one particularly important sentence in the book: “In all fighting, direct methods may be used for joining battle, but indirect methods will be needed to secure victory.”

“Direct methods” refer to formations, involving the fundamentals of an enterprise, such as teams, financial situation, products, supply chain, in-store retail displays, management, incentives, etc. Whereas, “indirect methods” are about seizing victory by a surprise move, which is what we should lay our stress on. The argument that follows this statement revolves around the latter.

Sun Tzu wrote with economy, but elaborated on “indirect methods” because they are simply too important to be explained in a few words.

Our reports for companies in the past focused on the “fit” among a company’s activities, which is part of “direct methods”. Later, as the limitations of “direct methods” alone became apparent, we started combining “war preparation reports” with “campaign reports”. A “war preparation report” specifies what each department should do to make incremental progress and train employees, while a “campaign report” explores how we should fight an actual battle and win by novelty.

The “war preparation-campaign” methodology is Kmind’s invention inspired by The Art of War. Campaign reports cover unexpected moves, coordination across departments, how to be like water on the battlefield, how to deal a “deadly blow”, and how to reshape the industry landscape as much as possible to secure a win.

CE: Most people only look at war preparation reports, which are the direct part of strategy. But without indirect methods, war preparation would be meaningless. Today, The Art of War has become a popular read in the entrepreneurial community, but it’s also misread by many. How can this be avoided?

Weishan: First of all, do not read The Art of War for the sake of quick success. The less purposeful and utilitarian you are, the better you will be at putting it to use, as the book is more about enlightening readers, rather than teaching us specific moves or secret tricks. It appears to be directionless and vague, but upon closer examination is certainly meaningful and insightful. You have to let it grow on you and get in touch with its true essence. Instead of seeking quick success and instant benefits, allow it to inspire and enlighten you.

Secondly, the first chapter of the book, the “Five Fundamentals and Seven Stratagems”, is very important. The “Five Fundamentals”, namely the five factors of “Morality, Heaven, Earth, the Commander, and Method and Discipline”, are especially noteworthy. “Morality”, in particular, is unfathomable to many. It’s actually about winning the hearts and minds of people, as it is in war. As we have mentioned earlier, the one who wins the hearts of the people wins the world. The same goes for running a business. You have to figure out exactly how to resonate with the minds of consumers before everything else can unfold. “Morality” is the key to all the other factors, but most people fail to even grasp the meaning of the first word.

“Morality” is clearly explained in The Art of War: “Morality causes the people to be in complete accord with their ruler, so that they will follow him regardless of their lives, undismayed by any danger.” In other words, you have to be on the same page as the people in order to win a battle. Thirdly, the thirteen chapters are well-structured, with a thorough interpretation of competition, strategy, and tactics, and should therefore be understood as an organic whole. Only by mastering the system can we draw inferences for other cases from one instance, rather than just quoting a few snippets.

CE: How will The Art of War inspire companies that have achieved 10 billion in scale?

Weishan: Human nature has its inherent weaknesses. Reaching 10 billion in revenue creates a magnified halo effect, causing outsiders, local governments, and various organizations to see a company differently. As a result, the company itself can easily slip into complacency, sloth, and twisted behavior.

Meanwhile, as companies grow in scale and profitability, more money, including social capital, will be readily available to them. At this point, you have to take extra caution as you move into new territory. Generally speaking, when you think you are wise, you are not far away from making mistakes. This is when you should keep an “empty cup” mentality and exercise great care.

In China, we have a lot of sayings that warn of such risks, including those in The Art of War. A careful and earnest reader of the book will feel humbled and less self-righteous. It contains so much nourishment for the mind that when you understand it, you stop clinging to your own ideas. It puts sparkling ideas in writing, such as rules for winning and losing battles. You know what leads to failure when you’ve read it thoroughly.